Phy5670/Bose-Einstein Condensation in Spin-gaped Systems: Difference between revisions

| (41 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

Bose-Einstein theory describes the behaviour of integer spin objects (bosons). This theory predicted the so-called Bose-Einstein Condensation (BEC) phenomenon. Bose Einstein condensates is one of exotic ground states in strongly correlated systems. At first, this condensation concept was applied to dilute gases of bosons which are weakly interacting. Those gases were confined in an external potential and cooled to temperatures very near to absolute zero. These cooling bosonic atoms then fall (or "condensate") into the lowest accessible quantum state, resulting in a new form of matter. One example of these gases is helium-3. | Bose-Einstein theory describes the behaviour of integer spin objects (bosons). This theory predicted the so-called Bose-Einstein Condensation (BEC) phenomenon. Bose Einstein condensates is one of exotic ground states in strongly correlated systems. At first, this condensation concept was applied to dilute gases of bosons which are weakly interacting. Those gases were confined in an external potential and cooled to temperatures very near to absolute zero. These cooling bosonic atoms then fall (or "condensate") into the lowest accessible quantum state, resulting in a new form of matter. One example of these gases is helium-3. | ||

Not long after the aplications of Bose and Einstein statistics to photons and atoms, Bloch applied the same concept to excitations in solid. He explained that the state of misaligned spins in a ferromagnet can be regarded as magnons, quasiparticles with integer spin and bosonic statistics. In 1965 paper, Matsubara and Matsuda pointed out the correpondences between a quantum ferromagnet and a lattice Bose gas <ref name="Matsubara" | Not long after the aplications of Bose and Einstein statistics to photons and atoms, Bloch applied the same concept to excitations in solid. He explained that the state of misaligned spins in a ferromagnet can be regarded as magnons, quasiparticles with integer spin and bosonic statistics. In 1965 paper, Matsubara and Matsuda pointed out the correpondences between a quantum ferromagnet and a lattice Bose gas <ref name="Matsubara" />. | ||

The similarity between the Bose gases and magnons suggests that magnons can undergo a process like Bose-Einstein condensation. However, in this case we are only considering simple spin systems, if we want to assume more realistic cases, such factors like anisotropies could restrict the usefulness of BEC concept. | The similarity between the Bose gases and magnons suggests that magnons can undergo a process like Bose-Einstein condensation. However, in this case we are only considering simple spin systems, if we want to assume more realistic cases, such factors like anisotropies could restrict the usefulness of BEC concept. | ||

Nevertheless, the analogy between bosons and spins has been very useful in antiferromagnetic systems which closely spaced pairs of spins <math>S={1 \over 2}</math> form with a singlet <math>S=0</math> ground state and triplet <math>S=1</math> excitations called magnons (some people call them triplons). Some examples of this system are <math>TlCuCl_3</math> and <math>BaCuSi_2O_6 | Nevertheless, the analogy between bosons and spins has been very useful in antiferromagnetic systems which closely spaced pairs of spins <math>S={1 \over 2}</math> form with a singlet <math>S=0</math> ground state and triplet <math>S=1</math> excitations called magnons (some people call them triplons). Some examples of this system are <math>TlCuCl_3</math> and <math>BaCuSi_2O_6</math>. | ||

Here I present an overview of BEC in antiferromagnetic systems. | Here I present an overview of BEC in antiferromagnetic systems. | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

=Bosons in Magnets= | =Bosons in Magnets= | ||

In this part we will explain the basics of magnon BEC in real dimerized antiferromagnets, such as <math>TlCuCl_3</math> and <math>BaCuSi_2O_6</math>. The lattice of magnetic ions can be regarded as a set of dimers carrying <math>S={1 \over 2}</math> each. We assume the Hamiltonian is in the form <ref name="Giamarchi" | In this part we will explain the basics of magnon BEC in real dimerized antiferromagnets, such as <math>TlCuCl_3</math> and <math>BaCuSi_2O_6</math>. The lattice of magnetic ions can be regarded as a set of dimers carrying <math>S={1 \over 2}</math> each. We assume the Hamiltonian is in the form <ref name="Giamarchi" />. | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 25: | ||

where <math>J_0</math> is the intra-dimer exchange coupling which is positive because this is antiferromagnetic system. <math>J_{mnij}</math> denotes the spin-spin interaction coupling, <math>\mu_B</math> is the usual Bohr magneton, and <math>H</math> denotes an external magnetic field in z-direction. For the indexes, <math>i,j</math> are number dimers, and <math>m,n=1,2</math> denote their magnetic sites. | where <math>J_0</math> is the intra-dimer exchange coupling which is positive because this is antiferromagnetic system. <math>J_{mnij}</math> denotes the spin-spin interaction coupling, <math>\mu_B</math> is the usual Bohr magneton, and <math>H</math> denotes an external magnetic field in z-direction. For the indexes, <math>i,j</math> are number dimers, and <math>m,n=1,2</math> denote their magnetic sites. | ||

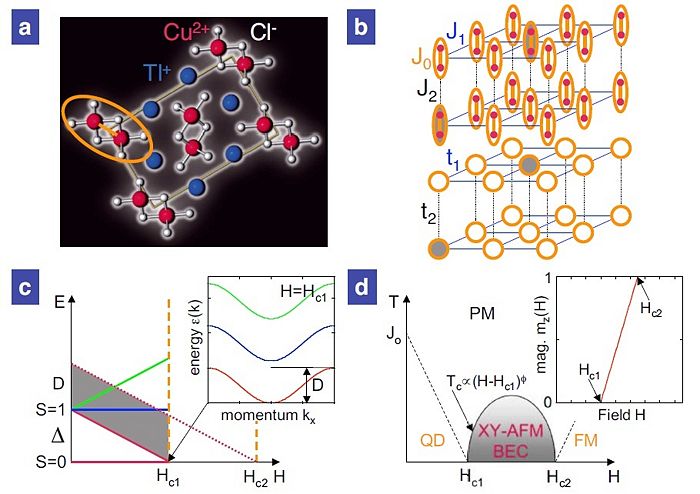

Here, the intra-dimer exchange is the strongest interaction. The system is antiferromagnetic which means that its isolated dimer has a ground state with total spin <math>S=0</math> and a triply degenerate excited state of spin <math>S=1</math> and energy <math>J_0</math> (Fig. 1c). In the quasiparticle language, the triplet states can be identified with the presence of triplons which are <math>S=1</math> bosonic particles, and the singlet states are states with the absence of triplons (Fig. 1b). With the assumption that inter-dimer interactions are weak, non-magnetic singlets ground state is disordered down to zero kelvin temperature with no long-range magnetic ordering. The triplon interacting with each other through weak interdimer couplings <math>J_{1,2,...}>0</math>.The interdimer couplings <math>J_{1,2,...}</math> can be constructed by summing over spin-spin interactions <math>J_{mnij}</math> (Fig. 1b). In the case of dimers forming a square lattice, the energy of a triplon with spin projection <math>S^z=0, \pm 1</math> is <ref name="Giamarchi"> | Here, the intra-dimer exchange is the strongest interaction. The system is antiferromagnetic which means that its isolated dimer has a ground state with total spin <math>S=0</math> and a triply degenerate excited state of spin <math>S=1</math> and energy <math>J_0</math> (Fig. 1c). In the quasiparticle language, the triplet states can be identified with the presence of triplons which are <math>S=1</math> bosonic particles, and the singlet states are states with the absence of triplons (Fig. 1b). With the assumption that inter-dimer interactions are weak, non-magnetic singlets ground state is disordered down to zero kelvin temperature with no long-range magnetic ordering. The triplon interacting with each other through weak interdimer couplings <math>J_{1,2,...}>0</math>.The interdimer couplings <math>J_{1,2,...}</math> can be constructed by summing over spin-spin interactions <math>J_{mnij}</math> (Fig. 1b). In the case of dimers forming a square lattice, the energy of a triplon with spin projection <math>S^z=0, \pm 1</math> is <ref name="Giamarchi" />. | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

where <math>\mathbf k =(k_x,k_y)</math> is the wavevector of particle, a is the lattice constant, and <math>D=4J_1</math> is the bandwidth (Fig 1.c). The dispersion relation of the triplons and singlet-triplet correlations can be measured directly by inelastic neutron scattering <ref name="Cavadini" | where <math>\mathbf k =(k_x,k_y)</math> is the wavevector of particle, a is the lattice constant, and <math>D=4J_1</math> is the bandwidth (Fig 1.c). The dispersion relation of the triplons and singlet-triplet correlations can be measured directly by inelastic neutron scattering <ref name="Cavadini" />. | ||

With the assumption that the system is isotropic, the spin singlet ground state is separated from the first excited triplet by a gap <math>\Delta</math> (Fig. 1c). The external magnetic field reduces the gap between singlet and triplet states according to <ref name="Tachiki" /> | |||

<math> | <math> | ||

| Line 42: | Line 41: | ||

When <math>\Delta(h)=0</math>, the system undergoes the antiferromagnetic ordering in which can be viewed as triplons condensation <ref name="Nikuni" | When <math>\Delta(h)=0</math>, the system undergoes the antiferromagnetic ordering in which can be viewed as triplons condensation <ref name="Nikuni" />. We can see clearly that the external magnetic field controls the density of triplons. From figure 1c , the excitation energy of triplons with <math>S^z=1</math> is lowered and eventually crosses zero as the magnetic field increases. There are two critical magnetic fields <math>H_{c1}</math> and <math>H_{c2}</math> in the phase diagrams (Fig 1d). We take consideration at <math>T=0 K</math>, below <math>H_{c1}</math> the system is in disordered phase, the magnetization <math>m_z(H)</math> is zero and only singlets exist. Between <math>H_{c1}</math> and <math>H_{c2}</math> , the magnetization starts increasing and the triplon band fills up (Fig. 1c). Above <math>H_{c2}</math>, the triplon band is full and the magnetisation saturates. | ||

The bosonic nature of triplons is guaranted by the simple fact that spin operators of two different dimers commute. However, the bosonic representation of dimers require a hard-core constraint to exclude states with more than quasi-particle per dimer. | The bosonic nature of triplons is guaranted by the simple fact that spin operators of two different dimers commute. However, the bosonic representation of dimers require a hard-core constraint to exclude states with more than quasi-particle per dimer. | ||

=BEC of Triplons= | =BEC of Triplons= | ||

[[Image:Spin-gap.jpg|thumb|700px|centre|BEC of magnons in dimerized quantum antiferromagnets (from Giamarchi, T. Ruegg, C. & Tchernyshyov, O. ''Nature Phys.'' '''4''', 198 (2008)): ('''a''')Dimers in the real material <math>TlCuCl_3</math> with <math>S=1/2</math> from Cu<math>^{2+}</math> ions and superexchange via Cl<math>^-</math>. ('''b''') Dimers on a square lattice with dominant antiferromagnetic intradimer interaction <math>J_0</math> and interdimer interactions <math>J_i</math>. Triplet states (gray, top) are mapped on quasi-particle bosons (triplons, bottom). ('''c''') Zeeman splitting of the triplet modes with gap <math>\Delta</math> and bandwidth <math>D</math> at <math>\mathbf k_0 = (\frac{\pi}{a}, \frac{\pi}{a})</math>. Dispersion of triplons at the critical field <math>H_{c1}</math>. ('''d''') Resulting phase diagram with paramagnetic (PM), quantum disordered(QD), field-aligned ferromagnetic (FM), and canted-antiferromagnetic(XY-AFM) phase, where BEC of magnons occurs. Close to <math>H_{c1}</math> and <math>H_{c2}</math> the phase boundary follows a power law <math>(T_c\propto H-H_{c1})^\phi</math> with a universal exponent <math>\phi=2/3</math> for BEC of magnons. Magnetisation curve <math>m_z(H)</math> for 3D dimer spin system with plateau at <math>m_z=0,1</math> (gapped).]] | |||

With the bosonic picture, the Hamiltonian in eq. (1) is more conveniently written in the second-quantized form | With the bosonic picture, the Hamiltonian in eq. (1) is more conveniently written in the second-quantized form | ||

| Line 60: | Line 62: | ||

where <math>h=g\mu_B H</math> is the effective field and <math>a_i^\dagger (a_i)</math> is the creation (annihilation) operator that creates (annihilates) a boson on dimer <math>i</math>. Hamiltonian above tells us that the external magnetic field H acts as a chemical potential which at low magnetic fields is prohibitively high and prevents bosons population, permitting population only above <math>H_{c1}</math>.In this sense, the density of bosons is directly controlled by the magnetic field. Referring to figure 1b, the bosons move on the lattice with kinetic energy provided by the <math>t_{ij}</math> term which is defined by the transverse component of the inter-dimer interactions <math>J^{x,y}_{1,2,..}</math> .The term <math>U_{ij}</math> is to account the hard-core property of bosons. The <math>U_{ij}</math> term acts as short-range repulsion arising from the ''z''-components <math>J^{z}_{1,2,...}</math> of interdimer interactions. | where <math>h=g\mu_B H</math> is the effective field and <math>a_i^\dagger (a_i)</math> is the creation (annihilation) operator that creates (annihilates) a boson on dimer <math>i</math>. Hamiltonian above tells us that the external magnetic field H acts as a chemical potential which at low magnetic fields is prohibitively high and prevents bosons population, permitting population only above <math>H_{c1}</math>.In this sense, the density of bosons is directly controlled by the magnetic field. Referring to figure 1b, the bosons move on the lattice with kinetic energy provided by the <math>t_{ij}</math> term which is defined by the transverse component of the inter-dimer interactions <math>J^{x,y}_{1,2,..}</math> .The term <math>U_{ij}</math> is to account the hard-core property of bosons. The <math>U_{ij}</math> term acts as short-range repulsion arising from the ''z''-components <math>J^{z}_{1,2,...}</math> of interdimer interactions. | ||

Below the first critical field (<math>H_{c1}</math>), the state of each dimer is singlet and the system as a whole is a quantum-disordered paramagnet. When the field reach <math>H_{c1}</math>, Bose condensate of triplons start to be formed. Since the bottom of the triplon band is located at a nonzero wavevector <math>\mathbf{k_0}= ({\pi \over a}, {\pi \over a})</math> (Fig 1c.), the wavefunction of the triplon varies in space <math>e^{i\mathbf{k_0\cdot r}}</math>. In this condition, the condensates start to form, the phase of a dimer can be approximately expressed as a superposition of the singlet state and the lowest energy state of triplet <math>S^z=+1</math>, i.e. <math>|\phi\rangle_i = \alpha_i(H) |0,0 \rangle_i + \beta_i(H) |1,1 \rangle_i</math>. The coefficients <math>\alpha_i</math> and <math> | Below the first critical field (<math>H_{c1}</math>), the state of each dimer is singlet and the system as a whole is a quantum-disordered paramagnet. When the field reach <math>H_{c1}</math>, Bose condensate of triplons start to be formed. Since the bottom of the triplon band is located at a nonzero wavevector <math>\mathbf{k_0}= ({\pi \over a}, {\pi \over a})</math> (Fig 1c.), the wavefunction of the triplon varies in space <math>e^{i\mathbf{k_0\cdot r}}</math>. In this condition, the condensates start to form, the phase of a dimer can be approximately expressed as a superposition of the singlet state and the lowest energy state of triplet <math>S^z=+1</math>, i.e. <math>|\phi\rangle_i = \alpha_i(H) |0,0 \rangle_i + \beta_i(H) |1,1 \rangle_i</math>. The coefficients <math>\alpha_i</math> and <math>\beta_i</math> should be depend on the external magnetic field since the field controls the density of triplons <ref name="Giamarchi2" /> <ref name="Matsumoto" /> <ref name="Matsumoto2" />. | ||

In spin language, the condensate corresponds to a spontaneous magnetic order formed by the transverse spin components <math>\langle S^x_i\rangle</math> and <math>\langle S^y_i \rangle$</math>, violating the rotational <math>O(2)</math> symmetry of the Hamiltonian. in anology with traditional BEC, we can express the transverse spin components as <math>\langle S_i^x+iS_i^y \rangle</math> which can be regarded as a <math>U(1)</math> order parameter. The phase corresponding to the angle of the spin in the <math>XY</math> plane is thus the phase of the wavefunction in the boson language. At <math>{H_{c1}}</math> the paramagnetic phase at low fields makes a transition into a canted antiferromagnet with long-range magnetic order in the plane perpendicular to the field <ref name = "Giamarchi2" />(Figs. 1d ). The staggering of the transverse components of magnetisation reflects a nonzero wavevector of the condensate <math>\mathbf k_0</math>. | |||

At <math>T=0</math> and <math>H = {H_{c1}}</math> occurs Quantum Critical Point (QCP) which is the location of a zero-temperature phase transition driven solely by quantum-mechanical fluctuations . The critical properties of the magnet in the vicinity of this phase transition are governed by the BEC universality class of the QCP. It should be noted that close to <math>{H_{c1}}</math> the bosons are extremely diluted, and the effects of the interaction become weak, despite its hard-core nature. Close to the QCP the phase boundary <math>T_c(H)</math> follows <ref name = "Giamarchi2" /> a power law <math>T_c \propto (H-{H_{c1}})^\phi</math> with a universal critical exponent <math>\phi=z/d</math>, which depends only on the dimensionality (<math>d</math>) and dynamical critical exponent <math>z=2</math> for a quadratic triplon energy band. The upper critical dimension for the QCP is <math>d_c=2</math>. | |||

As the last thing, below is a summary of the correspondence between a Bose gas and antiferromagnet <ref name="Giamarchi" />. | |||

{| | |||

|+ Table 1. Correspondence between a Bose gas and a quantum antiferromagnet. | |||

{|class="wikitable" style="background-color:#E6E6FA; color:black" cellpadding="30" cellspacing="0" border="1" | |||

|- | |||

! Bose gas | |||

! Antiferromagnet | |||

|- | |||

| Particles | |||

| Spin excitations (<math>S=1</math> quasi-particles) | |||

|- | |||

| Charge conservation U(1) | |||

| Rotational invariance O(2) | |||

|- | |||

| Condensate wavefunction <math>\langle \psi(\mathbf r) \rangle</math> | |||

| Transverse magnetic order <math>\langle S^x_i + iS^y_i\rangle</math> | |||

|- | |||

| Chemical potential <math>\mu</math> | |||

| Magnetic field <math>H</math> | |||

|} | |||

|} | |||

=References= | |||

1. Matsubara, T. & Matsuda, H. ''Prog. Theor. Phys.'' '''16''', 569 (1956). | |||

2. Giamarchi, T. Ruegg, C. & Tchernyshyov, O. ''Nature Phys.'' '''4''', 198 (2008). | |||

3. Cavadini, N. ''et al.'' ''Phys. Rev. B'' '''63''', 172414 (2001). | |||

4. Tachiki, M. & Yamada, T. ''J. Phys Soc. Jpn'' '''28''' 1413 (1970). | |||

5. Nikuni, T., & Oshikawa, M., Oosawa, A. Tanaka, H. ''Phys. Rev. Lett.'' '''84''', 5868 (2000). | |||

6. Giamarchi, T. Tsvelik, A. M. ''Phys. Rev. B'' '''59''', 11398 (1999). | |||

7. Matsumoto, M., Normand, B., Rice, T. M. & Sigrist, M. ''Phys. Rev. Lett.'' '''89''', 077203 (2002). | |||

8. Matsumoto, M., Normand, B., Rice, T. M. & Sigrist, M. ''Phys. Rev. B'' '''69''', 054423 (2004). | |||

Latest revision as of 16:54, 5 December 2010

Introduction

Bose-Einstein theory describes the behaviour of integer spin objects (bosons). This theory predicted the so-called Bose-Einstein Condensation (BEC) phenomenon. Bose Einstein condensates is one of exotic ground states in strongly correlated systems. At first, this condensation concept was applied to dilute gases of bosons which are weakly interacting. Those gases were confined in an external potential and cooled to temperatures very near to absolute zero. These cooling bosonic atoms then fall (or "condensate") into the lowest accessible quantum state, resulting in a new form of matter. One example of these gases is helium-3.

Not long after the aplications of Bose and Einstein statistics to photons and atoms, Bloch applied the same concept to excitations in solid. He explained that the state of misaligned spins in a ferromagnet can be regarded as magnons, quasiparticles with integer spin and bosonic statistics. In 1965 paper, Matsubara and Matsuda pointed out the correpondences between a quantum ferromagnet and a lattice Bose gas [1].

The similarity between the Bose gases and magnons suggests that magnons can undergo a process like Bose-Einstein condensation. However, in this case we are only considering simple spin systems, if we want to assume more realistic cases, such factors like anisotropies could restrict the usefulness of BEC concept.

Nevertheless, the analogy between bosons and spins has been very useful in antiferromagnetic systems which closely spaced pairs of spins Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S={1 \over 2}} form with a singlet Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S=0} ground state and triplet Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S=1} excitations called magnons (some people call them triplons). Some examples of this system are Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle TlCuCl_3} and Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle BaCuSi_2O_6} .

Here I present an overview of BEC in antiferromagnetic systems.

Bosons in Magnets

In this part we will explain the basics of magnon BEC in real dimerized antiferromagnets, such as Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle TlCuCl_3} and Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle BaCuSi_2O_6} . The lattice of magnetic ions can be regarded as a set of dimers carrying Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S={1 \over 2}} each. We assume the Hamiltonian is in the form [2].

Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mathbf H = \sum_{i} J_{0} \, \mathbf S_{1,i} \cdot \mathbf S_{2,i} + \sum_{\langle mnij \rangle} J_{mnij} \, \mathbf S_{m,i} \cdot \mathbf S_{n,j} - g \mu_B H \sum_{\langle mi \rangle} S^z_{m,i},\quad\quad\quad (1) }

where Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle J_0}

is the intra-dimer exchange coupling which is positive because this is antiferromagnetic system. Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle J_{mnij}}

denotes the spin-spin interaction coupling, Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mu_B}

is the usual Bohr magneton, and Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle H}

denotes an external magnetic field in z-direction. For the indexes, Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle i,j}

are number dimers, and Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle m,n=1,2}

denote their magnetic sites.

Here, the intra-dimer exchange is the strongest interaction. The system is antiferromagnetic which means that its isolated dimer has a ground state with total spin Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S=0} and a triply degenerate excited state of spin Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S=1} and energy Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle J_0} (Fig. 1c). In the quasiparticle language, the triplet states can be identified with the presence of triplons which are Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S=1} bosonic particles, and the singlet states are states with the absence of triplons (Fig. 1b). With the assumption that inter-dimer interactions are weak, non-magnetic singlets ground state is disordered down to zero kelvin temperature with no long-range magnetic ordering. The triplon interacting with each other through weak interdimer couplings Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle J_{1,2,...}>0} .The interdimer couplings Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle J_{1,2,...}} can be constructed by summing over spin-spin interactions Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle J_{mnij}} (Fig. 1b). In the case of dimers forming a square lattice, the energy of a triplon with spin projection Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S^z=0, \pm 1} is [2].

Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \varepsilon(\mathbf k) = J_0 + J_1[\cos{(k_x a)} + \cos{(k_y a)}]- g \mu_B H S^z, \quad\quad\quad (2) }

where Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \mathbf k =(k_x,k_y)}

is the wavevector of particle, a is the lattice constant, and Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D=4J_1}

is the bandwidth (Fig 1.c). The dispersion relation of the triplons and singlet-triplet correlations can be measured directly by inelastic neutron scattering [3].

With the assumption that the system is isotropic, the spin singlet ground state is separated from the first excited triplet by a gap Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Delta} (Fig. 1c). The external magnetic field reduces the gap between singlet and triplet states according to [4]

Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Delta (h)= \Delta - g\mu_B H.\quad\quad\quad (3) }

When Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Delta(h)=0}

, the system undergoes the antiferromagnetic ordering in which can be viewed as triplons condensation [5]. We can see clearly that the external magnetic field controls the density of triplons. From figure 1c , the excitation energy of triplons with Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S^z=1}

is lowered and eventually crosses zero as the magnetic field increases. There are two critical magnetic fields Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle H_{c1}}

and Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle H_{c2}}

in the phase diagrams (Fig 1d). We take consideration at Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle T=0 K}

, below Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle H_{c1}}

the system is in disordered phase, the magnetization Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle m_z(H)}

is zero and only singlets exist. Between Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle H_{c1}}

and Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle H_{c2}}

, the magnetization starts increasing and the triplon band fills up (Fig. 1c). Above Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle H_{c2}}

, the triplon band is full and the magnetisation saturates.

The bosonic nature of triplons is guaranted by the simple fact that spin operators of two different dimers commute. However, the bosonic representation of dimers require a hard-core constraint to exclude states with more than quasi-particle per dimer.

BEC of Triplons

With the bosonic picture, the Hamiltonian in eq. (1) is more conveniently written in the second-quantized form

where is the effective field and is the creation (annihilation) operator that creates (annihilates) a boson on dimer . Hamiltonian above tells us that the external magnetic field H acts as a chemical potential which at low magnetic fields is prohibitively high and prevents bosons population, permitting population only above .In this sense, the density of bosons is directly controlled by the magnetic field. Referring to figure 1b, the bosons move on the lattice with kinetic energy provided by the term which is defined by the transverse component of the inter-dimer interactions .The term is to account the hard-core property of bosons. The term acts as short-range repulsion arising from the z-components of interdimer interactions.

Below the first critical field (), the state of each dimer is singlet and the system as a whole is a quantum-disordered paramagnet. When the field reach , Bose condensate of triplons start to be formed. Since the bottom of the triplon band is located at a nonzero wavevector (Fig 1c.), the wavefunction of the triplon varies in space . In this condition, the condensates start to form, the phase of a dimer can be approximately expressed as a superposition of the singlet state and the lowest energy state of triplet , i.e. . The coefficients and should be depend on the external magnetic field since the field controls the density of triplons [6] [7] [8].

In spin language, the condensate corresponds to a spontaneous magnetic order formed by the transverse spin components and , violating the rotational symmetry of the Hamiltonian. in anology with traditional BEC, we can express the transverse spin components as which can be regarded as a order parameter. The phase corresponding to the angle of the spin in the plane is thus the phase of the wavefunction in the boson language. At the paramagnetic phase at low fields makes a transition into a canted antiferromagnet with long-range magnetic order in the plane perpendicular to the field [6](Figs. 1d ). The staggering of the transverse components of magnetisation reflects a nonzero wavevector of the condensate .

At and occurs Quantum Critical Point (QCP) which is the location of a zero-temperature phase transition driven solely by quantum-mechanical fluctuations . The critical properties of the magnet in the vicinity of this phase transition are governed by the BEC universality class of the QCP. It should be noted that close to the bosons are extremely diluted, and the effects of the interaction become weak, despite its hard-core nature. Close to the QCP the phase boundary follows [6] a power law with a universal critical exponent , which depends only on the dimensionality () and dynamical critical exponent for a quadratic triplon energy band. The upper critical dimension for the QCP is .

As the last thing, below is a summary of the correspondence between a Bose gas and antiferromagnet [2].

| Bose gas | Antiferromagnet |

|---|---|

| Particles | Spin excitations ( quasi-particles) |

| Charge conservation U(1) | Rotational invariance O(2) |

| Condensate wavefunction | Transverse magnetic order |

| Chemical potential | Magnetic field |

References

1. Matsubara, T. & Matsuda, H. Prog. Theor. Phys. 16, 569 (1956).

2. Giamarchi, T. Ruegg, C. & Tchernyshyov, O. Nature Phys. 4, 198 (2008).

3. Cavadini, N. et al. Phys. Rev. B 63, 172414 (2001).

4. Tachiki, M. & Yamada, T. J. Phys Soc. Jpn 28 1413 (1970).

5. Nikuni, T., & Oshikawa, M., Oosawa, A. Tanaka, H. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 5868 (2000).

6. Giamarchi, T. Tsvelik, A. M. Phys. Rev. B 59, 11398 (1999).

7. Matsumoto, M., Normand, B., Rice, T. M. & Sigrist, M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 077203 (2002).

8. Matsumoto, M., Normand, B., Rice, T. M. & Sigrist, M. Phys. Rev. B 69, 054423 (2004).

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMatsubara - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGiamarchi - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCavadini - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTachiki - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNikuni - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGiamarchi2 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMatsumoto - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMatsumoto2